The Koban is the heart of community policing in Japan.

Remember community policing? Yes, it was a big buzzword in the U.S. during the 90s, a decade that featured a brutal police beating of Rodney King, an unarmed black man, which sparked riots in Los Angeles. The idea was to have policemen be participating members of a neighborhood, an integral part of community life. This would promote good relations between citizens and the men in uniform, acquaint the police with the citizens and unique activities of the people living near the community policing stations, giving them first-hand familiarity with the “players” there, good and bad. People would see police as humans just like them, police would experience citizens on a personal level. Moreover, if there were a problem requiring their attention, the police would be in the vicinity right on the scene.

It turned out to be more of a PR stunt in most cities in the U.S. and the approach finally buckled under the tensions it created, fueled by suspicion, lack of real trust, the sense that the cops weren’t there to help but to spy on the locals, using their insertion in the locale to better subject the everyday citizens to the strong-arm tactics and “establishment” bullying law enforcement is often rightly accused of.

Community policing is not just a PR campaign here in Japan. It’s a reality. If there’s a problem and it’s not an emergency, you turn to the officers at the local Koban to get help. They truly are members of the community, living in the housing usually at the rear of the building, often with their own families.

There are a number of these in my home town here, and thousands all across Japan. Even in the big cities. I’ve seen them in Osaka and Tokyo.

Let me tell a story to see how this approach actually functions here. And please understand that I’m not trying to portray myself as some hero. What I did in this situation is exactly what 99.999% of all of the folks living here would do.

Masumi and I were on our way to a nearby town, if I recall, to visit her mom. It was a nasty day, rainy and windy, visibility was poor. I was driving. We approached an intersection and as I slowed down, I looked out the side window of her Mazda. This is what I saw.

Obviously, that was not the woman. I Photoshopped the pic to illustrate what happened.

I immediately braked, signaled to the car behind me to stop. Then I went over to the body laying in the road.

It was an elderly lady, probably in her 80s, and she was conscious, laying exactly as you see in the above pic, just staring straight into to cold, wet pavement.

The man in the car which was following me came over. We talked to the lady and helped her to her feet. She was fine. Just confused and lost.

There was a Koban not more than 100 meters away, around the corner of the intersection.

We walked the lady there, sat her down. The police officer on duty got a blanket, probably one of his own from the private quarters, and it greatly helped the lady warm up. It was a cold, miserable day.

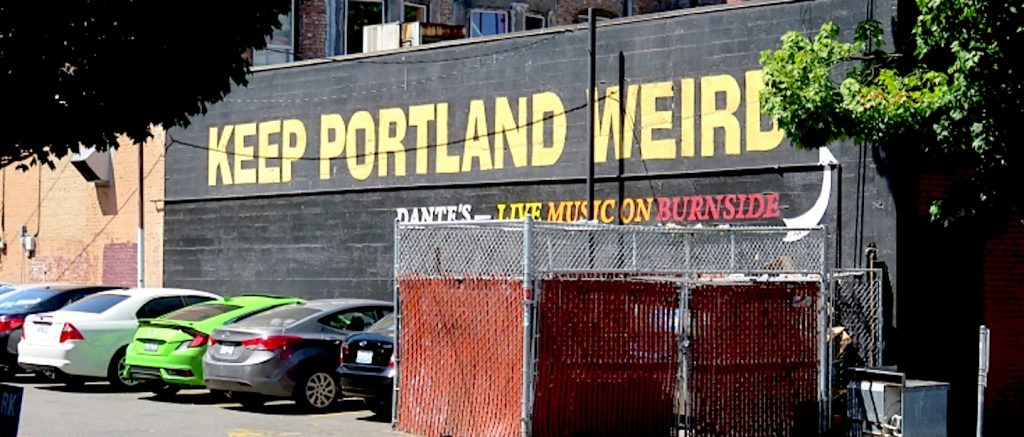

Before I go on, let me show you the tiny strip on this narrow street where she was laying.

It was a miracle she wasn’t run over! As I already mentioned, the day this happened was gray and cloudy, it was raining, visibility was very poor. And this is a well-traveled road. To make things even more precarious, she was dressed in a long overcoat a color that almost matched to pavement.

The police officer tried to get some basic information from her. Sadly, I think she was a victim of severe dementia. But . . . because he was right there in the community, he knew exactly who to call. Yes, there’s a nursing home nearby. One phone call later, the staff at the nursing home confirmed a lady fitting her description was missing. They sent someone over and took her back to the comfort of her residential care facility.

See how easy this works? No calls to central headquarters, checking databases for missing persons, trying to piece together a narrative to explain and identify this lost woman. Being right there in the neighborhood cuts through a lot of red tape and guesswork.

The officer interviewed Masumi and I, as well as the other driver, got all the details, filled out the requisite paperwork — Japanese love paperwork! — and thanked us for our service. He was very professional. It was obvious he took his job seriously and liked his work.

Community policing works. Especially if the police are dedicated and honest.

Life In Japan: Public Restrooms

Japanese folks will wonder why in the world am I writing about public restrooms. They take it for granted that when you gotta go, you just go. Restrooms are plentiful, clean, safe, well-maintained and open to the public everywhere here.

I can explain why this is a big deal. I’ll answer with a question: Have you ever tried to pee in New York City?

Without checking into a hotel?

Without sitting down to a meal at a restaurant?

Without buying an ensemble you didn’t need at a department store?

Or let’s say you do happen to stumble on one of the extremely scarce public toilets.

If you don’t encounter a homeless family who have set up housekeeping . . .

. . . if you don’t see a junkie shooting up over in the corner . . .

. . . if you don’t have to step over dead body or two . . .

. . . if you don’t find perverts having sex through a glory hole between adjoining stalls . . .

. . . then the stench will drive you out, because the place hasn’t been cleaned since they laid off some janitorial city worker six months ago to give tax breaks to Wall Street execs.

Let me be clear.

I consider peeing-on-demand a basic human right. Like breathing, going to the bathroom is not a lifestyle choice.

Japan completely respects the inevitability and the all-too-often urgency of nature’s call.

Here in my hometown of Tambasasayama, in the eight or ten block area which comprises the center of our town, I counted no less than five public toilet facilities. As restrooms go, they’re fine. Nothing fancy. But clean, properly kept up to the high standards and hygienic expectations of the citizens here.

Additionally, there are restaurants, temples, public buildings, stores which have toilets. I’ve never seen a ‘Restrooms For Customers Only’ sign anywhere in Japan.

Along with the five public toilets downtown is an outdoor one at a supermarket . . .

. . . another at a 7-11 convenience store . . .

. . . and yet another at a curios shop/restaurant . . .

. . . all publicly accessible, no questions, no hassles.

Could relief be any more accessible? Adult diapers? (Ugh!)

Granted, there are those who might accuse me of focusing too much here on the mundane. Come on! Toilets?

Just remember. Sometimes it’s taking care of the little, simple things in life, which makes the much bigger, more complex things possible. Try to enjoy that stroll through Greenwich Village or taking in the sites at Times Square when you’ve had to hold it in for four hours.