This is not going to be a formal or particularly thorough discussion of Western art forms here in Japan. In fact, it’ll be largely anecdotal but nevertheless I believe an accurate portrayal of the odd juxtaposition of the unambiguously Western art forms and styles on a culture with its own unique rich heritage, which not in the least resembles or had been influenced by Euro-America until Japan finally was “opened” to the West 165 years ago. Significant Westernization occurred in two peak periods: From 1868-1900 during the Meiji restoration, and from 1945 until the present following the Allied victory over Japan ending World War II. This resulted in modern Japan, where Kibuki Theater and geishas co-exist with American-style pro wrestling and Japanese hip-hop.

My wife, Masumi, perfectly embodies the contradiction, though unlike most contradictions there are no discernible incompatibilities or anomalies. ‘Contradiction’ is really the wrong term. Because all that is contradicted are my expectations. I’ll get to Masumi in Part 2, as she deserves an entire article of her own.

Long before I ever knew I’d be coming to and then settling in Japan, I received some early inklings about Japan’s love affair with the West, meaning not just its superficial courtship of dress and hair styling, but its thorough embrace of both formal and pop arts.

Long before I ever knew I’d be coming to and then settling in Japan, I received some early inklings about Japan’s love affair with the West, meaning not just its superficial courtship of dress and hair styling, but its thorough embrace of both formal and pop arts.

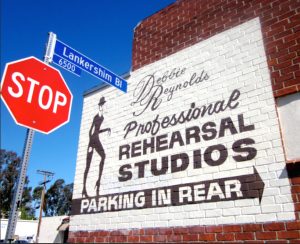

I was taking jazz dance classes at Debbie Reynolds Studios — yes, that Debbie Reynolds — in Los Angeles, and one summer a plane load of young Japanese jazz dancers (late teens, early twenties) packed the classes. To put it mildly, I was amazed, stunned, awed! Not only were they physically perfect as dancers — slender; strong, sinewy  muscles; elegant posture; each individually radiating grace and vigor, coupled with a charming shyness — they could really dance!

muscles; elegant posture; each individually radiating grace and vigor, coupled with a charming shyness — they could really dance!

I also wistfully recall one of my favorite dance teachers mentioning that he loved taking on guest teaching positions in Japan, because the students were so fiercely dedicated and disciplined. When he’d return from such an assignment, he’d jokingly count off our dance routines in Japanese: ichi, ni, san, yon! While we thought that was pretty darn cute, I never gave it all that much thought. Japan just wasn’t on my radar screen back then.

At the same time, it was no secret that Western performers, in particular pop and rock acts — everyone from the Beatles, Cindi Lauper, Santana, Carpenters, Michael Jackson, ABBA, Rolling Stones, and Avril Lavigne, to Ozzy Osborne and Bob Dylan — loved playing Japan. All reported that Japanese audiences were enthusiastic and they felt truly appreciated.

Get this: Even jazz artists like Chick Corea, Art Blakey, Oscar Peterson, Sonny Clark, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Bill Evans, and John Coltrane had and often still have impressive fan bases in Japan.

Get this: Even jazz artists like Chick Corea, Art Blakey, Oscar Peterson, Sonny Clark, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Bill Evans, and John Coltrane had and often still have impressive fan bases in Japan.

Much more popular and widespread than jazz is classical music. During my first full year in Japan, I was invited to attend a piano recital. I don’t know what that sounds like to you but I assumed it would be a bunch of cute kids fumbling their way through simple songs, their adoring parents taking videos for the grandparents. Right. Try concert-level Chopin, Mozart, Brahms, Beethoven. And these were just high school students! Turns out that studying piano from a very young age is pervasive here — piano lessons with a focus on eventually mastering the legends, for example, those just mentioned.  Japan has, of course, already produced a number of widely-acclaimed, world-class musicians and composers, and believe it or not, Tokyo alone hosts “no fewer than eight full-size, full-time, fully professional orchestras, collectively providing more than 1,200 concerts a year.”

Japan has, of course, already produced a number of widely-acclaimed, world-class musicians and composers, and believe it or not, Tokyo alone hosts “no fewer than eight full-size, full-time, fully professional orchestras, collectively providing more than 1,200 concerts a year.”

Getting back to dance . . .

I’ve been a longstanding fan. I saw my first ballet in high school. Not only did I take some jazz classes for ten years starting in 1985, I even dabbled in both modern and ballet over the years. The great ballet dancers like Baryshnikov, Nureyev, Fonteyn, Markova, have always fascinated me.

That being the case, about a year ago I became acquainted with a fellow who is not well known in the West, but in my opinion may be one of the best ballet dancers ever! His name is Kumakawa Tetsuya. Born in Hokkaido, Japan, he studied in England and became a principal dancer with the Royal Ballet, before returning to Japan to form his own ballet company. Feast your eyes on a man who seems able to rewrite the laws of gravity . . .

. . . and make challenging moves breathtakingly beautiful and inhumanly effortless . . .

There are two Japanese ballerinas, who despite being in my opinion, among the best in the world, are not exactly household names in the West.

Kuranaga Misa . . .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gnEXTcBojk

. . . and Nakamura Shoko . . .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxiHzXM7yxQ

Pretty amazing, eh?

If there is an unspoken, but nonetheless dutifully-regarded and rigorously-observed rule in play governing just about every act, action, activity, ambition, and endeavor here, it’s this: Whatever the Japanese do, they do well. They are maddening perfectionists. Many would say this is why Japan was able to rebuild so quickly and totally after World War II, eventually becoming the world’s third largest economy. Others would attribute Japan’s high suicide rate to the extreme pressures of high performance and achievement.

Both would be right.

Life In Japan: Western Arts – Pt 2

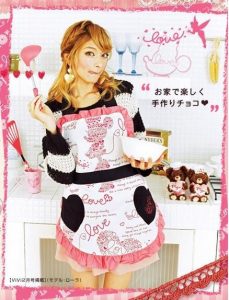

This is a photograph of my wife, Masumi, at age 20 singing Il Bacio by Italian composer Luigi Arditi. She has been singing opera all her life, plays beautiful classical piano, and dances ballet as a pastime.

I find it a fascinating question why Japan is so enamored with Western art forms, not that I’ve made any progress coming close to a conclusive answer.

All of this is the normal cross-pollination of cultures, which occurs when borders become more permeable, trade encouraged and opportunities for tourism pervasive.

Yet, there are some things that either don’t translate well, resist integration, because they are simply entirely incompatible with established social traditions and cultural legacies.

That, of course, is an example of steadfast social training.

But I would have suspected that another type of training would be just as determinant. I’m referring to ear training.

The Japanese scales — actually all Asian scales — are microtonal. When they don’t sound randomly annoying, they sound intentionally grating, at least to my Western ears. I’m just not used to hearing — literally not trained to hear — the two or three notes that purposely occur between C and C# or between E and F. I’ll admit that in my band days I was often accused of tuning my guitar microtonally but that was just a way of saying I had a really lousy sense of pitch.

At the same time, Western music and the fundaments for making it have gripped Japan. And in every form: pop, rock, jazz, classical, blues, rap, hip hop.

Recognize that there are Western arts chauvinists who would say this is inevitable. They will make a very convincing argument that Western scales are fundamentally superior, more accessible and natural to the homo sapiens physiological mechanisms involved in processing music.

There is a very appealing mathematics to the Western scale. The 37th key on an 88-key piano is A. It vibrates at 220 cycles per second (Hz). The 49th key is also an A, but it’s one octave above, vibrating at 440 Hz. The 25th key is an A that’s one octave below, vibrating at 110 Hz. Nifty, eh? This suggests the mathematical foundation underlying the tonal relationships among the notes of the Western 12-tone scale. In fact, this holds together quite nicely until we get to the very bottom and top of the useful musical range. The math has to be adjusted a bit. Pianos tuned to mathematical perfection tend to sound sharp at the very top and bottom, requiring at the extremes that the scale be “stretched” to make the piano sound in tune to the human ear. This is not a flaw in the mathematics. It’s a consequence of the physical properties of the strings of the piano, a stiffness which causes inharmonicity at the extremes. Thus this need to “temper” the scale doesn’t diminish the essential elegance of the theory.

Zeebra, a very popular hip hop artist here in Japan (Click on pic to see a video.)

So as I say, it’s easy for music experts in the West, the ones juxtaposing Fibonacci spiral graphs on the human cochlea, to posit the intrinsic superiority of a viola over a shamisen, an oboe over a hichiriki, or a flugel horn over a horagai, put in the service of playing the Sound of Music.

They may be right. But the bottom line is there’s really no way to objectively settle the matter. An anecdotal aside: I mentioned to my wife the other day that one of my English students sings Japanese folk songs to me. The lady is very proud of her voice and the songs she had spent her life mastering. My wife asked me if they were traditional or modern folk songs. I didn’t know there was a difference. Turns out that traditional folk songs are the original microtonal versions. Now there are modern versions of those folk songs which make the melodies fit the Western 12-note scale. Think about that! They take these amazing songs from time immemorial and update them — literally Westernize them musically — for the prevailing tastes of contemporary Japanese listeners.

This seems to suggest some greater inherent appeal in the mathematically-based music system of the West. But I say it’s just a sign of the times. We have Burger King in Beijing, KFC in Kuala Lumpur, McDonald’s in Moscow. There are rappers and hip hop artists in every country that has electricity, except maybe Bhutan.

My wife, Masumi, of course continues to teach Westernized music to elementary students in a nearby community here in Japan, as part of the official school curriculum. The kids play recorders, xylophones, accordions, keyboards, snares, bass drums, bongos, congas, and other percussion — all instruments from the West. And since she still loves singing, she even gives an occasional vocal performance under the auspices of the vocal teacher she’s studied with for three decades. Usually she sings opera, though she occasionally helps me out on my original songs, in my informal home recording studio.

Here she is earlier this year in concert at a gathering in Osaka.